What the FFF? Or, how to avoid triggering Fight, Flight, or Freeze responses in others

/What the FFF are you talking about, Halelly?

We humans are tricky creatures. Even though we have these awesome brains that enable us to devise unbelievable innovations like flying a space ship to the moon or unmanned drones to deliver your next pizza, we also get spooked out very easily by things that threaten our survival. And when we do, we experience one of three infamous types of reactions:

Fight: we attack the thing or person threatening us,

Flight: we run like hell from the thing or person threatening us, or

Freeze: we impersonate a deer in the headlights and lose the ability to move or think straight for a few seconds or minutes (that feel like hours and days...).

Fight, Flight or Freeze responses are as old as dirt, yet here to stay

This self-protection mechanism is as old as we are a species and was designed to help us stay alive. It helped us back in our caveman days. If you were walking around the jungle or the prairie back in the good 'ol days, and you heard a rustling sound from the nearby pile of dry leaves or bushes, you knew that there was a pretty good chance there was a saber tooth tiger about to turn you into human sashimi. You had three choices: attack the tiger (bad choice!); freeze and play dead (bad choice!); or run like hell (ding ding ding ding ding!).

My assumption is that thus far, I've not revealed anything earth-shatteringly new to you, am I right?

Well, here's the thing: While we all recognize that we experience this reaction when, say, an attacker is approaching you with a drawn weapon or a large animal is chasing you, we don’t necessarily equate this response as a valid reaction to a social or emotional offense. But what’s amazing is that we now have unmistakable proof (thanks to the field of neuroscience) that what many had previously just observed and hypothesized is true: We experience threat in the same place in the brain, often with the same intensity, whether it is a threat to our physical well-being or our emotional or social well-being. So whether you are excluded from a team meeting or are threatened at gun point, as far as your brain is concerned, the threat is real, and the response is “What the FFF!!”

It only takes a fifth of a second for your brain to perceive a potential threat and react! Tweet This!

FFF Responses (aka Threat Responses) occurs in the oldest part of our brain, the limbic system. The key player in this role is the amygdala, a small almond-shaped area of our brain that helps us remember whether something is a threat to be avoided or a reward to be sought after. And since it is charged with keeping you safe and alive, it works fast: studies show it takes about a fifth of a second for your brain to process cues, perceive threat or reward, and act.

Then, your biology kicks into higher gear

Once there is a perceived threat, your brain arranges for extra resources for your fight or flight: it lines up oxygen and glucose it anticipates you’ll need and makes them LESS available for your prefrontal cortex – the part of your brain used for rational thinking and executive functions like making decisions and solving problems.

In addition, you experience an overall increase in brain activity that causes you to focus very narrowly and miss a bunch of more subtle information that’s available, making you less aware or capable of solving problems in a linear, rational way. You become more likely to jump to conclusions.

You’re also more likely to generalize and make the wrong connections, as well as ‘play it safe’ and recoil from any opportunities that are not a sure bet.

And, as if that’s not debilitating enough, you’re also more likely to become much more defensive and pessimistic, assuming negative intent on others’ part as well as assuming the worst of the situation and its root causes or being less likely to see opportunities for solutions.

Oy.

So how do we avoid triggering this FFF threat response in others?

By now you may recognize that it’s not very difficult to trigger this response in others, and that it does not produce optimal results for yourself, the team, or the organization. Since the slightest things could trigger this kind of threat response, and kick off this FFF chain of events, we have an interest in doing what we can to avoid triggering threat in others if at all possible. Let’s look at how to do that.

Use the SCARF model to avoid or minimize threat response

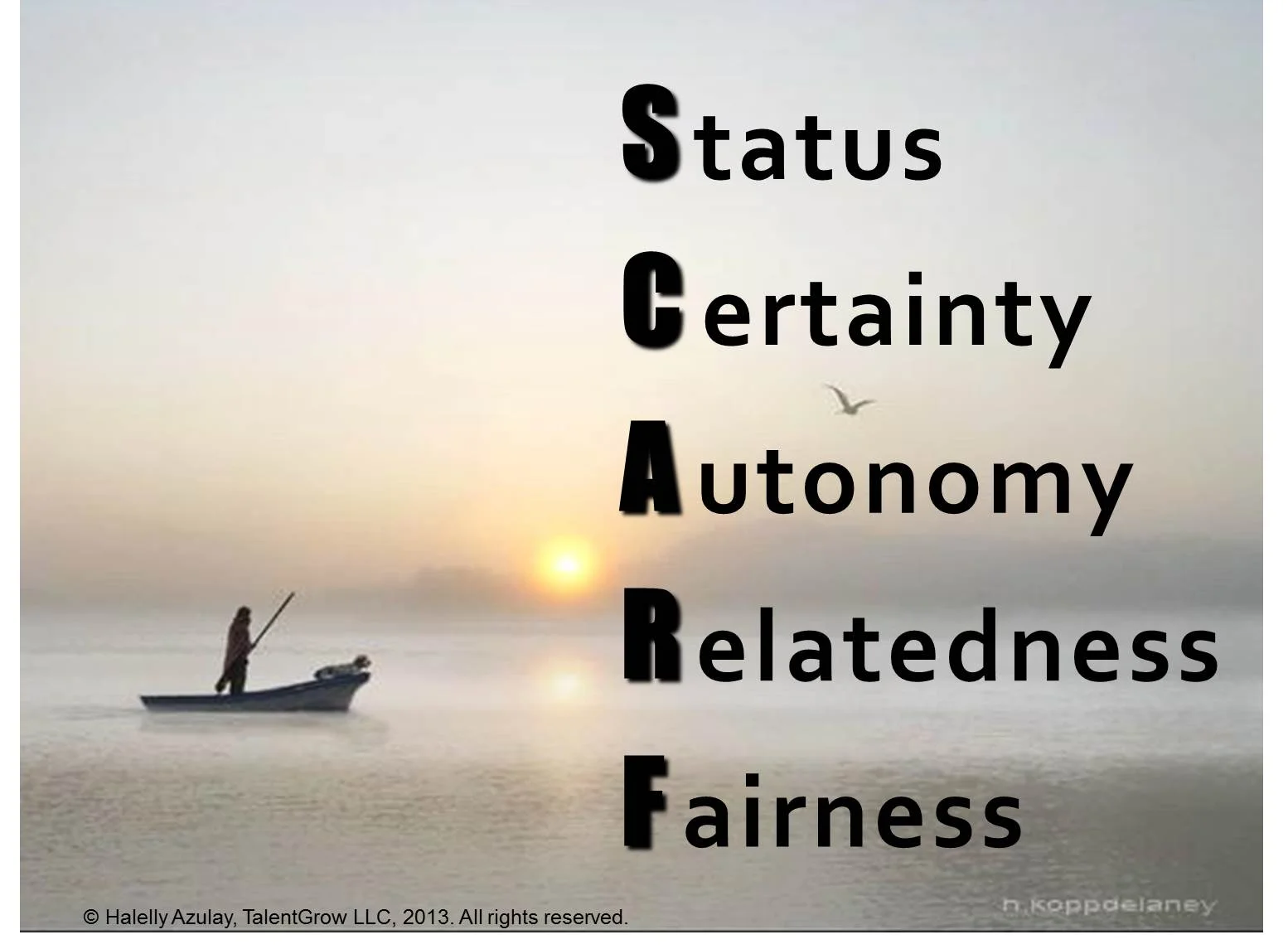

A helpful way to learn and recall some of the key domains that trigger a threat responses, is the SCARF acronym: Status, Certainty, Autonomy, Relatedness, and Fairness, coined by neuroscientist Dr. David Rock, which I’ve briefly mentioned when I wrote about the 3 Keys to Communication Success. These five domains help us remember what is really important to humans and each of these domains can trigger a threat reaction if it is placed in perceived jeopardy.

So in order to minimize or avoid saying or doing something that causes your colleagues, boss, staff or anyone you’re communicating with to go into “What the FFF” mode, try to minimize threatening their SCARF domains and even try to increase their sense of reward in as many of them as possible to offset any threats.

Let me briefly describe each of these domains and give a quick example for what might threaten it and what might prop it up.

Status: We want to ensure that we’re not on the bottom of the social hierarchy of any group we belong to. We want to either feel like we’re on equal footing, or better (higher status) than others in our group. In the caveman days this helped us ensure we don’t get left behind as tiger treats, but in today’s workplace, you might threaten status by simply excluding someone from a meeting invitation or skipping over their input during a meeting. To raise status, aside from giving them a raise or a better job title of course, you can actually give people the opportunity to learn and develop new skills and then pay attention and remark on their improvement. You can also offer positive feedback (just ensure you follow my STS Formula!), especially if it’s done in front of others, to prop up their sense of status.

Certainty: We don’t like not knowing what’s going on and what to expect. It makes us feel anxious and unsafe. We even prefer to know bad things are about to happen than to be in the dark – at least we can plan and prepare ourselves. To avoid triggering a threat response, be upfront and transparent as much as possible about information, changes, and expectations.

Autonomy: We like to feel like we’re in control of our lives. Feeling out of control means we are not sure we can freely respond to actual threats (as in physical threats) and this spills over into our need for autonomy for emotional and social well-being also. Whenever possible, figure out ways to allow people to choose – even among two limited options – rather than just telling them what to do or the best solution. The more people can be involved in choosing and designing what will happen to them, the less threatened their need for autonomy will be.

Relatedness: We’re social animals – when we were cave dwellers, we needed to ensure we could rely on others for our safety and survival, and things are not that different now that we’re office-building dwellers. We need to feel like we belong to the “in-group”. If we feel no connection with others, we feel lonely and that triggers a threat response. Create opportunities for people to connect on a human level and find things they have in common. It actually releases the hormone oxytocin, which creates positive emotions!

[Listen to my conversation with Dr. Paul Zak about his research on oxytocin and trust: Ep056: How to build high trust workplace cultures with neuroscientist Paul Zak.]

Fairness: We need to feel like we’re being treated fairly – and to see that others around us are also treated that way. Things that are unfair trigger a threat response and we react pretty strongly to injustice. Make every effort to establish clear expectations, ground rules, and equitable working conditions.

So there you have it – our brains are wired to avoid threats and to react to perceived threats by fighting them, fleeing from them, or sometimes freezing from the shock of them. This threat response is not limited just to physical danger and has been shown to occur in social and work settings. Avoiding triggering this kind of social threat response can help you avoid throwing those around you into working with diminished thinking resources and helps you get more rational, better quality, and less disruptive responses to your work interactions.

Have you ever triggered a FFF response in someone at work? How did you know – what were some of the signs? How did you react? Tell your anecdote in the comments below (but don’t mention any names!), or ask a question!

Fighter planes photo by Flickr Creative Commons User Spigoo

Get more tips, news, and articles like this in Halelly’s free weekly newsletter. If you use this link [http://eepurl.com/PTIRn] to sign up (it’s fast and easy!), we’ll send you a free bonus guide on “How to Influence Even Without Authority”!

Sign up to my free weekly newsletter and get more actionable tips and ideas for making yourself a better leader and a more effective communicator! It’s very short and relevant with quick tips, links, and news about leadership, communication, and self-development. Sign up now!

Also, subscribe to my podcast, The TalentGrow Show, on iTunes to always be the first in the know about new episodes of The TalentGrow Show! http://apple.co/1NiWyZo

You Might also Like These Posts:

3 Keys to Communication Success

What's at the Intersection of Non-Verbal Communication and Emotional Intelligence Skillfulness?